Afghanistan is one of the poorest countries in the world – now things could get even worse

The Taliban, having taken over Afghanistan, will inherit an economy that is among the world’s most ramshackle.

That may surprise many given the billions of dollars spent by the United States and its allies in the country during the last two decades.

Afghanistan live updates: All the latest as the Taliban establish new government

Most of that money, though, was invested in trying to train the Afghan police and military and establish a coherent rule of law.

Despite the construction of a number of high-rise buildings, chiefly in Kabul, rather less was spent on initiatives, such as infrastructure improvements, that would have boosted growth longer term.

That is not to say there was not some improvement after the US and its allies kicked out the Taliban.

According to World Bank data, Afghan GDP – the total value of goods and services produced in an economy – grew from $4.055bn in 2002 to $20.561bn in 2013.

But growth slowed dramatically when, in 2014, most foreign combat troops – a key source of income – left the country with the departure of the UN-backed International Security Assistance Force.

Afghanistan’s GDP growth fell from around 14% in 2012 to as little as 1.5% by 2015.

There was a subsequent recovery from 2016 onwards but, as of 2020, the economy was still worth just $19.807bn.

It slipped back into recession last year due to the COVID-19 outbreak and an intensification of political unrest that disrupted exports.

The country remains among the poorest in the world.

The latest World Bank data suggests that only six countries worldwide – among them Burundi, Somalia, and Sierra Leone – have a lower GDP per head (roughly speaking the value of a country’s economy divided by its population) than Afghanistan.

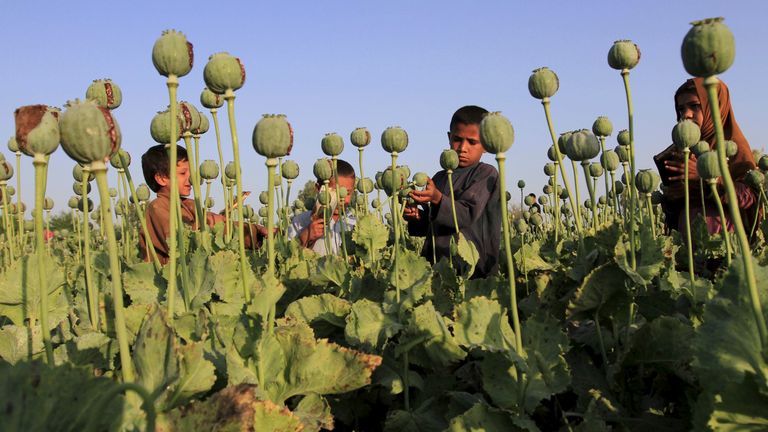

At least a fifth of Afghan GDP is reckoned to come from the opium trade, much of which has been controlled by the Taliban, helping arm the group.

In all, agriculture makes up around half of economic activity in Afghanistan, while it also accounts for at least half of all employment in a country where two in five people are jobless.

Apart from opium, wheat is the key agricultural export, although there has also been diversification in recent years into more valuable crops such as walnuts, almonds, pistachios, saffron, pomegranates and raisins, despite increasing amounts of land being given over to opium cultivation.

Moreover, a lack of investment in cold stores and packaging facilities has held back Afghanistan’s ability to make more from fruit and vegetable exports, with at least a quarter of agricultural products reckoned to deteriorate after being harvested to such an extent that they cannot be sold.

After agriculture, the key source of income for Afghanistan is overseas aid, which has traditionally covered about three-quarters of Afghan government spending.

This, though, has been falling in recent years and can be expected to almost completely dry up now that the Taliban have seized control.

That is not to say that, even under Taliban control, there will not be economic opportunities.

Afghanistan is rich in mineral resources – the value of which was put at $1trn a decade ago – including deposits of lithium and cobalt, both key components in electric vehicle batteries, gold, copper and iron ore.

Those riches were charted by Soviet geologists following the invasion 40 years ago and, more recently, by the Pentagon, which, in an internal document in 2010, suggested Afghanistan had potential to become “the Saudi Arabia of lithium”.

Unfortunately, Afghanistan’s ability to exploit those resources will be hampered by a lack of transport infrastructure, a developed electricity grid and technical expertise, with few mining engineers prepared to set foot in the country even before the Taliban came to power.

Even China Metallurgical Group, which has owned the rights to exploit one of Afghanistan’s biggest copper deposits since 2007, has not done so due to concerns over security.

China, which is already the biggest foreign investor in Afghanistan, would be a logical partner for the Taliban if the country’s considerable mineral reserves are ever to be exploited but it is likely to drive a hard bargain and will require strong guarantees on security.

Ashraf Ghani, the former president, refused a request from China to cut royalty rates some years ago.

Nor have these mineral riches helped Afghanistan much to date.

Much of what mining exists in the country is illegal, not only depriving the government of royalties, but also providing income to insurgents.

Greater than Afghanistan’s mineral wealth is its human capital.

It is a young country, with getting on for two-thirds of the population under the age of 25, as well as an increasingly educated one.

From a situation where one in five Afghans were illiterate after the Taliban were kicked out, there has been a massive expansion in education, with 10 times as many universities as there were in 2001.

Among the key beneficiaries have been women and girls, who were previously deprived of education under the Taliban, but who now once again face the prospect of being banned from either education or employment.

A continuation of the Taliban’s previous ban on allowing women to work would be the biggest single obstacle to economic growth in future.

Others are likely to include the country’s relatively poor health.

Life expectancy is lower than elsewhere in South Asia.

The Taliban takeover does not only have consequences for Afghanistan’s own pitiful economy.

There are also huge economic implications for the country’s neighbours, in particular Pakistan, where there are already estimated to be nearly 1.5 million Afghan refugees.

Millions more can be expected to head off as they seek to escape the Taliban.

Afghanistan’s neighbours to the north, including Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, will also have similar concerns.

Added to this will be the risk that some projects planned by the Ghani government in partnership with Afghanistan’s neighbours may now not come to fruition.

Chief among these was a railway, running via Kabul, connecting Mazer-i-Sharif, close to the Uzbek border, with Peshawar in Pakistan.

This was expected to be of huge benefit not only to landlocked Afghanistan, but also its neighbours in terms of its ability to transform trade and reduce the cost of doing it.

Afghanistan’s economy was already in a parlous state.

But that is not to say it could not become even weaker under the Taliban.