Bank of England signals pause in rate rises as Putin’s war heightens recession risk

When the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee met to consider interest rates last month, Ukraine was not even part of the debate.

What a difference six weeks make.

At Wednesday’s meeting of the Bank’s decision makers, the Russian invasion was in the first line of the minutes as the Bank took the unprecedented step of commenting on geopolitics, condemning Russia’s “unprovoked invasion”.

It was a fitting preface to a discussion dominated by the implications of war in Europe.

“The invasion of Ukraine has led to further large increases in energy and other commodity prices including food prices,” the committee concluded.

“It is also likely to exacerbate global supply chain disruptions, and has increased the uncertainty around the economic outlook significantly. Global inflationary pressures will strengthen considerably further over coming months.”

The dramatic shift in focus in a few short weeks demonstrates just how completely the advent of all-out conflict, and the wave of sanctions imposed on Russia in response, has upended economic expectations for the year ahead.

The impact of Russia’s aggression is a red thread that runs through every paragraph of minutes that forecast disruption, rising prices and uncertainty at every turn. Many of the impacts have exacerbated existing economic pressures.

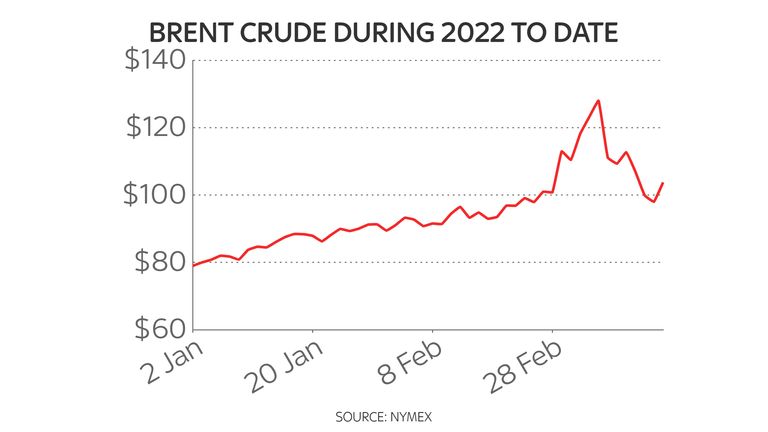

The invasion has deepened the ongoing energy crisis that dominated much of the discussion at the Bank’s last meeting, with oil prices soaring and the US, EU and UK all vowing to reduce reliance on Russian hydrocarbons.

As a consequence, the Bank believes energy prices could be “substantially higher” in October when Ofgem sets a new price cap.

That will be a major driver of inflation, expected to peak in June at 8% and possibly higher later in the year.

Commodity prices have also risen, particularly for food, a real-world household impact that families were already beginning to feel before countries that are the source of 30% of the world’s wheat began fighting in the breadbasket of Europe.

The Bank’s response to this uncertainty is modest and expected, a 0.25% increase – the third consecutive rise that returns rates to their pre-pandemic level.

The rate rises are not an attempt to limit increases in many costs as they are outside its control.

This is about curbing inflation expectations as high pay increases, to help accommodate bigger bills, will only add to the inflation problem further down the track.

Eight of nine members voted in favour with just one arguing for a pause at the existing 0.5%.

Their expectation of what happens next has changed however.

“Further modest tightening in monetary policy may be appropriate,” a step back from the suggestion it was “likely” reached at their last meeting.

The concern is that adding to the squeeze on living standards by raising rates, which raises borrowing costs and mortgage bills for those not on fixed rate deals, could choke off an already fragile recovery after two years of COVID.

The war means the Bank’s ability to influence that has been much reduced.

Attention will now turn to the House of Commons next Wednesday when Rishi Sunak delivers his ‘mini budget’ spring statement to MPs.

The chancellor is being urged to help ease the price burden by all corners of the economy.