China has its own fuel crisis – powered by coal shortage and climate commitments

While the UK obsesses about panic-buying of petrol, there are fuel crises going on elsewhere around the world, no more so than in China.

There, a series of power cuts has hit millions of homes and businesses, particularly big industrial users of energy.

Of the 31 provinces on mainland China, 16 have been rationing power, affecting areas that make up two-thirds of the country’s economic output.

The upshot is that a number of forecasters are now predicting China’s economy will grow less rapidly this year than expected.

It has become a commonplace complaint from countries in the west that, while they strive to transition towards a zero-carbon future, their efforts are in vain because of the way China is building new coal-fired power stations.

So it is ironic that these power cuts are partly because many Chinese provinces are trying hard to meet emissions targets imposed by Beijing.

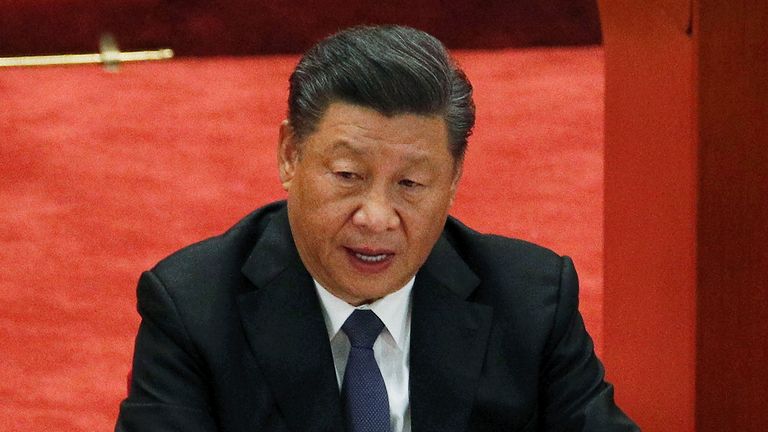

President Xi Jinping told the United Nations General Assembly a year ago that China was aiming to hit its peak in CO2 emissions before 2030 and was targeting carbon neutrality before 2060.

He meant it. As part of achieving these targets, Beijing is aiming to cut its energy consumption this year by 3%, but many provinces look like falling short of that climate goal.

Accordingly, power supplies are being cut, potentially with far-reaching implications. Suppliers to US tech companies including Apple and Tesla have been among those forced to suspend production due to power shortages.

The cuts also threaten to exacerbate the global chip shortages that have, for example, forced carmakers in Europe to suspend production.

Beijing’s seriousness about hitting these emissions targets has been hammered home in recent days.

The Global Times, a popular state-owned tabloid newspaper and a key plank of the government’s propaganda machine, wrote in an editorial on Tuesday: “China has to accelerate the development of nuclear energy, hydroelectric power, wind power, and solar power.

“Society needs to support the build-up of each type of clean energy. We should reduce the proportion of coal-fired power generation as soon as possible.

“We are destined to become a global superpower in terms of power generation, but we cannot always be a superpower with a high proportion of coal-fired power generation among major economies.”

Listen and subscribe to The Ian King Business Podcast here.

The editorial concluded: “We must plan carefully and bid farewell to the era of extensive power generation and use.”

It is therefore doubly ironic that the other reason for the power cuts China is currently enduring is coal itself.

The world may be trying to wean itself off coal but the price of the world’s least-loved commodity has soared this year as economies emerge from the pandemic and their industries fire up again.

The price of thermal coal, which is used to generate electricity, has more than doubled during the last 12 months reflecting higher demand, particularly from Asia, as well as some supply constraints caused by the fact there has been less investment in coal mines during the last decade.

The price of coking or metallurgical coal, which is used to produce steel, is also at a record level.

In China’s case, those problems have been made more intense by Beijing’s ban on coal imports from Australia. Chinese imports from the world’s second biggest producer have fallen by 99% this year following the ban, introduced last October, amid a deterioration in relations between the two countries sparked by Canberra’s calls for an investigation into the origins of COVID-19.

But China has struggled to source coal from other producers. It resumed coal imports from South Africa this year for the first time in six years and has also been buying more from producers such as Indonesia and Russia. In doing so, though, it faces competition from other countries, such as India, which are struggling to replenish their own coal stocks.

China’s own domestically-produced coal, meanwhile, is of insufficient calorific value – quality – to generate as much power as Australian coal. Added to this is the fact that, with temperatures still quite high, some Chinese utilities are trying to stockpile for the winter months.

All of which has left China short of coal and obliged it to seek alternative supplies of energy, chiefly liquefied natural gas (LNG), to heat homes and industries.

And this, in turn, is one reason why oil prices are surging around the world. Industrial businesses that might normally rely on LNG are, amid competition from China, seeking to use oil as an alternative.

A harsh winter would only make matters worse and which is why some analysts expect the price of oil will hit $90 a barrel before the end of the year.

It feels as though the global energy crunch is set to intensify. Only a mild winter, of the kind we experienced last year, is likely to change that.