Interest rate drumbeat grows louder as BoE governor warns it may ‘have to act’ over inflation

The drumbeat towards an interest rate rise from the Bank of England is growing ever louder.

Speaking on Sunday, the Bank’s governor, Andrew Bailey, gave his strongest hint yet that Bank rate is set to rise from 0.1%, where it has sat since March last year.

During an online panel discussion organised by the Group of Thirty, an independent global body that seeks to deepen understanding of global economic and financial issues, Mr Bailey warned that he and his colleagues on the monetary policy committee (MPC) would “have to act” in response to surging inflation.

He told the grouping, which includes a number of the world’s leading former central bankers, the Bank remained convinced that the recent rise in inflation was temporary and caused by the rapid bounce-back from the pandemic of the global economy.

But he admitted the recent surge in energy prices would make the rise in inflation bigger and longer-lasting than previously expected.

This, he added, raised the risk of higher inflation expectations – something the Bank watches carefully because of the impact it can have on wage demands and wage inflation.

Mr Bailey went on: “Monetary policy cannot solve supply-side problems – but it will have to act and must do so if we see a risk, particularly to medium-term inflation and to medium-term inflation expectations.

“And that’s why we at the Bank of England have signalled, and this is another such signal, that we will have to act.

“But of course that action comes in our monetary policy meetings.”

His comments have sparked a reaction in financial markets.

The futures market is now applying a probability of more than 90% to Bank rate rising to 0.25% at the MPC’s next meeting on 4 November.

Bank rate is now expected to be 0.5% by the end of February next year and more than 1% by the end of 2022.

Other financial instruments are also pricing in likely rises in interest rates.

The yield on gilts, UK government IOUs, has risen across a number of durations.

For example, the yield on 10-year gilts has risen from 1.105% at the close on Friday to as much as 1.173% today, while the yield on two-year gilts has surged from 0.585% at the close on Friday to as much as 0.748% today.

Jim Reid, head of global fundamental credit strategy at Deutsche Bank, said of Mr Bailey’s remarks: “It’s difficult to get much more explicit than this.”

Jeffrey Halley, senior market analyst at the brokerage OANDA, added: “Markets are locking and loading a hike before year-end from the Bank of England.”

Only on the foreign exchange markets has there been less of an impact.

That is because, against the possibility of an interest rate rise, traders also have to weigh the possibility that the UK is not just in for inflation, but the dreaded phenomenon of “stagflation”, the toxic combination of inflation and slow growth last seen in this country during the 1970s.

The UK would not be alone in raising interest rates.

A number of other central banks around Europe have done so since the pandemic, among them the Czech National Bank, which last month raised its main policy rate from 0.75% to 1.5% in what was its biggest hike in 24 years.

The MNB, Hungary’s central bank, has raised interest rates four times this year to take its main policy rate from 0.6% to 1.65%.

Iceland’s central bank has raised interest rates twice this year, taking its policy rate from 0.75% to 1.25%, while earlier this month the National Bank of Poland raised its main policy rate from 0.1% to 0.5% in what was its first rate rise in almost a decade.

Others to have moved recently include the National Bank of Romania, which just over a week ago raised its main policy rate from 1.25% to 1.5% and the Central Bank of Russia, which has so far raised rates four times this year to take its main policy rate from 4.5% to 6.75%.

Norges Bank, the central bank of Norway, meanwhile, last month abandoned its zero interest rate policy, taking its base rate to 0.25%.

Further afield, other central banks to have raised interest rates recently include those of Sri Lanka, South Korea and New Zealand, which hiked rates earlier this month for the first time in seven years in a bid to dampen its soaraway housing market.

Yet a move on rates is by no means guaranteed.

Some members of the monetary policy committee have made clear in recent days they would oppose an early interest rate rise.

For example, Silvana Tenreyro said last week that raising interest rates in response to what was only a temporary rise in inflation would be “self-defeating”, arguing that by the time interest rates were having a major effect on inflation, the effects of energy prices would already be dropping out of the inflation calculation.

Last week also saw Catherine Mann, one of the MPC’s newest members, making a similar point.

Also in the dovish camp is another external MPC member, Jonathan Haskel, whose previous speeches have suggested he fears an early interest rate rise would stifle growth.

Against them are ranged Michael Saunders, also an external member of the committee, who said two weeks ago that UK households needed to brace for “significantly earlier” interest rate rises than previously expected.

And Huw Pill, the Bank’s chief economist, suggested to MPs on the Treasury select committee earlier this month that the “current strength of inflation” looked to last for longer than expected.

That was taken as a sign that he favours an early move in Bank rate.

A third member of the MPC, Sir Dave Ramsden, who is the deputy governor for markets and banking, has also made similar observations.

With Sir Jon Cunliffe, the Bank’s deputy governor for financial stability, also thought to be in the dovish camp, an early rate hike will probably therefore require the support of both Mr Bailey himself and Ben Broadbent, the deputy governor for monetary policy.

There is, however, another option for the Bank if it wishes to tighten monetary policy without actually raising interest rates.

That would be for the MPC to vote not to go ahead with the remaining £50bn worth of asset purchases – quantitative easing (QE) in the jargon – that it is due to carry out before the end of the year.

The Bank could also stop rolling over its existing asset purchases.

At present, when a gilt held by the Bank under QE is repaid by the Treasury, the Bank reinvests the proceeds in the market on other gilts.

Were it to stop doing that, the Bank would be holding £37bn worth of gilts by the end of next year, which would be the equivalent of raising interest rates by nearly one-third of 1%.

But the market is now predicting that a straightforward rise in interest rates is the likeliest outcome.

Inflation is likely to come in at north of 4% when the next figures are published and that is even before other price increases that are in the pipeline.

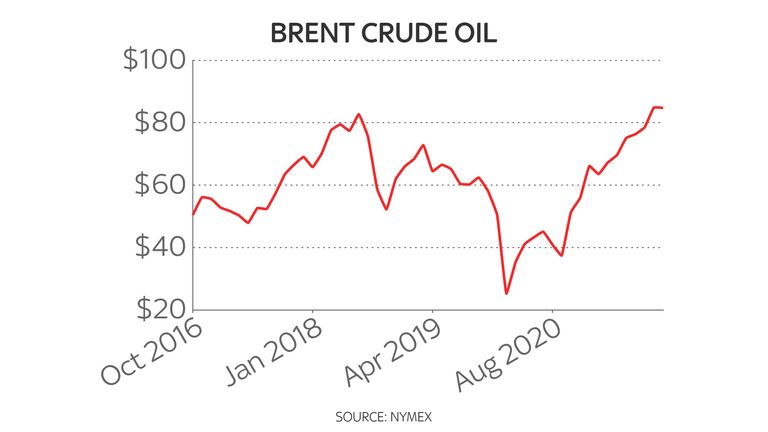

Ofgem’s energy price cap is likely to rise at the next review, as it does not currently reflect the recent increases in wholesale energy costs, with Brent Crude today hitting a level not seen since 4 October 2018.

The US contract, West Texas Intermediate, is currently at a seven-year high.

Council tax bills are set to rise sharply in the spring as councils seek to bring in more money to cover the rising cost of social care.

Meanwhile, with more than a million vacancies going unfilled, wage inflation in a whole range of occupations is creeping in.

The traditional response to any one of these factors would have, in the past, have been a rise in interest rates.

A higher Bank rate, leading to a higher mortgage rate, will doubtless come as a shock to the current generation of homeowners who have known nothing but ultra-low interest rates now for more than a decade.

It is, though, the way to bet.