Pound plunges as Bank of England resists pressure to raise interest rates

The Bank of England has surprised investors and economists by leaving interest rates on hold at 0.1% for at least another month.

However, the Bank used its quarterly Monetary Policy Report to signal that it was likely to increase borrowing costs in the “coming months”.

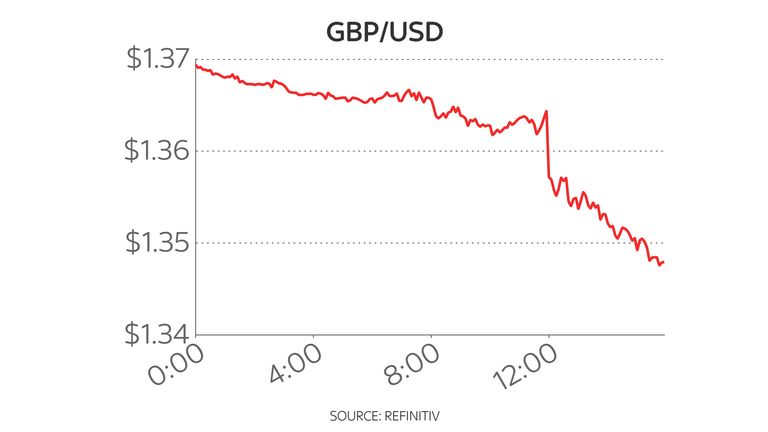

The decision pushed the pound lower by two cents against the US dollar to less than $1.35 since many investors had been expecting the Bank’s nine-member monetary policy committee (MPC) to increase Bank rate to 0.25% this month.

Sterling also fell by a cent versus the euro, to below €1.17, while in stock markets lenders Natwest, Lloyds and Barclays – whose profitability tends to be boosted by higher rates – saw their shares fall by 4% or more.

But Bank governor Andrew Bailey fought back amid accusations that he wrong-footed investors by signalling an imminent rate increase ahead of today’s decision.

Mr Bailey told Sky News that rate-setters still needed to see “hard evidence” on the state of the jobs market before any hike and that an increase would not directly address key supply chain issues that are key causes of the acceleration in price rises.

At a news conference following the announcement, Mr Bailey said the rates decision had been a “very close call” and rejected being characterised as an “unreliable boyfriend” in confounding market expectations – a charge that was previously levelled at his predecessor Mark Carney.

Seven members of the MPC voted to leave interest rates unchanged while two – Dave Ramsden and Michael Saunders – voted to increase them.

The 7-2 split is the same as the previous month.

The Bank said that it now expected the consumer prices index (CPI) measure of inflation to rise to 5% next year – among the highest price forecasts since the Bank was granted independence in 1997.

It cut its forecast for economic growth by a percentage point and pushed back the date at which the UK economy regains the level it was at before COVID and the lockdowns.

The Bank said much of these forecast changes could be attributed to problems in global supply chains, which have pushed up prices and limited the availability of goods, and to higher energy costs.

However it forecast that inflation would fall sharply towards the end of next year and said that it was quite plausible that if energy prices fell in line with market expectations, inflation could drop below its target next year.

The Bank had been widely expected to increase borrowing costs since the governor warned at an event last month that with inflation rising fast, it would “have to act” to bring prices under control.

Listen and subscribe to The Ian King Business Podcast here

In the MPC minutes, the Bank said: “The committee judged that, provided the incoming data, particularly on the labour market, were broadly in line with the central projections in the November monetary policy report, it would be necessary over coming months to increase Bank Rate in order to return CPI inflation sustainably to the 2% target.”

In an interview with Sky News, Mr Bailey said: “What we have signalled today is that we do think that interest rates will need to rise. We haven’t done it today.

“It was a very close call today, I should emphasise, and the reason we haven’t done it is because we still need, in our view, to see the hard evidence, particularly of the state in the job market in this country.”

Asked why the Bank did not raise interest rates today, despite predicting a rise in consumer price index inflation to 5%, Mr Bailey said: “We have to look at the causes of inflation.

“Many of the causes of inflation would not be tackled directly by raising interest rates.

“It wouldn’t produce more gas, wouldn’t produce more semiconductor chips, to allow more cars to come onto the market, for instance. It wouldn’t tackle any of those supply chain issues.

“Indeed, actually it would have a worse effect: it would raise interest rates, it would slow down the economy, and it would probably cause unemployment to rise.

“Now, we will have to take that step if we think that there is a risk to the economy in terms of it overheating, but it would not be the right answer to a shortage of gas to raise interest rates.

“If the only thing we have at the moment is a shortage of gas, that would not be the right answer.”