Ships avoiding Russia as sanctions impact revealed

Maritime trade with Russia has more than halved since the invasion of Ukraine began three weeks ago, new data reveals.

The dramatic fall in seaborne trade is three and half times greater than at the worst point during the COVID pandemic and follows a series of sanctions imposed on Moscow by Western countries.

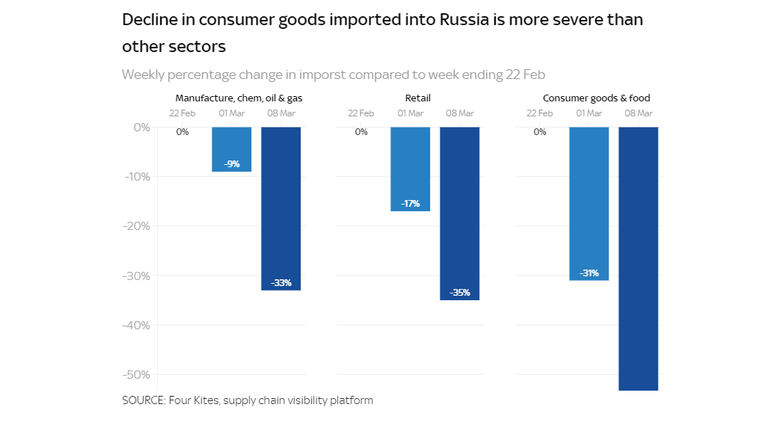

It could mean a shortage of goods in Russia’s shops in the coming days as retailers, manufacturers and businesses run out of warehouse stocks which trade analysts suggest are normally meant to last between one and three weeks.

How big is the decline in trade?

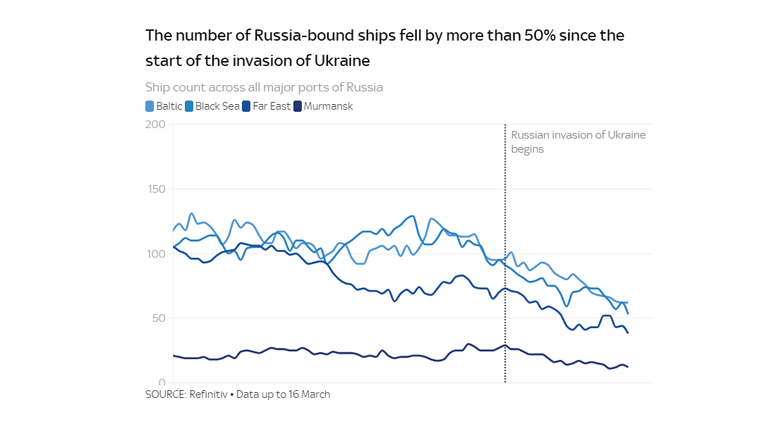

Before the invasion of Ukraine on the 24 February, the average number of ships bound for Russia had held steady at around 325. Since then, this has fallen by more than 55%, according to financial data provider Refinitiv.

“In my 20-year career, I have not seen this big of a drop into one destination, as we’ve seen over the last three weeks,” said Glenn Koepke, a general manager at FourKites, a supply chain technology platform.

It’s not only sanctions, but physical harm to ships and their crew, that are having an impact, particularly in the Black Sea.

Here, Russian naval forces have launched hundreds of missiles into Ukraine prompting many shipping companies either to cancel or reroute away from the area, driving a decline of 58% compared to the pre-invasion period.

The fall in trade at other Russian ports, many located thousands of miles away from the conflict, also points towards the effectiveness of sanctions applied by the US, UK, EU and other allies.

Ports in the Baltic Sea, like St Petersburg, responsible for a third of Russia’s nautical trade, now have 65% fewer ships making port calls, according to calculations by the investment bank UBS.

In the Pacific, the number of ships has declined by 52% since the war started. These ports, including Vladivostok, primarily receive cargo from China, Japan and South Korea.

The impact of sanctions on supply chains

The reduction in shipping trade has disrupted business supply chains in Russia, with imported goods becoming scarce.

Car maker Lada this week announced suspension of operations at three factories, the larger of which employs more than 30,000 people.

Western companies have turned away from Russia even in industries that have not been sanctioned.

These include dry commodities such as coal, grain and fertilisers, of which Russia is a major exporter.

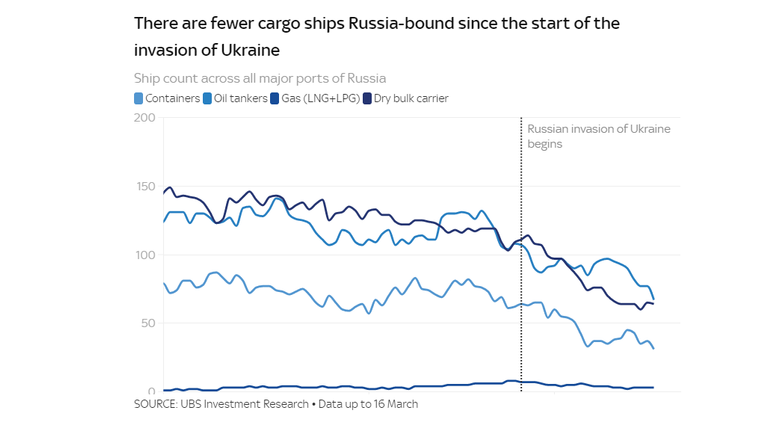

The number of container ships, oil tankers and dry bulkers, which account for three quarters of the Russia-bound fleet, has dropped between 40% and 60% since late February, according to UBS data.

This decline in ships carrying wheat and grain is likely to worsen global food security.

British supermarkets Sainsburys, Morrisons, Asda and Waitrose announced a ban on Russian-made vodka. Meanwhile, fast-fashion retailers ASOS and Boohoo suspended sales for Russian consumers.

Oil giant Royal Dutch Shell turned its back on all Russian oil and gas, which also have not been sanctioned, only a week after a public backlash over a Russian oil deal the company signed after the invasion began.

Mr Koepke suggests Western companies are concerned with the social impact and reputational risk of doing business with Russia.

“Generally war is just not a well-accepted position. The longer this goes on, the harder it will be for any company in any country to do business with Russia,” he said.

The West’s dependence on oil & gas

While the reduction in ships and problems in the supply chain might mean fewer goods for Russian consumers to buy, the rise in oil price could limit the impact of sanctions on the Russian government.

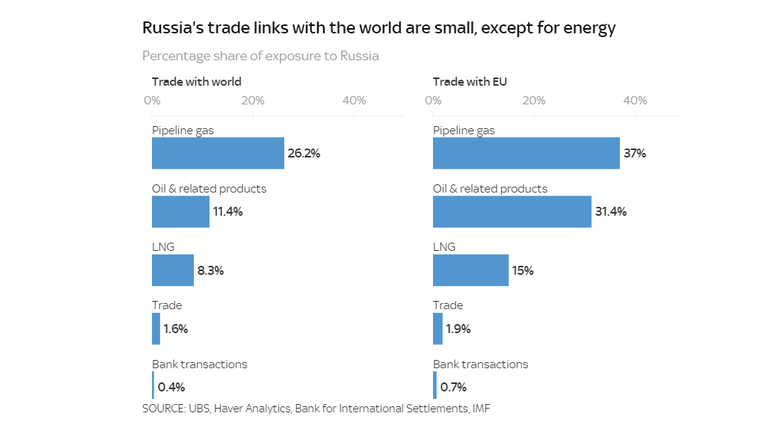

Russia produces a quarter of global pipeline gas and a tenth of global oil. Share of the trade with the EU in those sectors is even larger.

In October, the Russian Finance Ministry said it had an income of $500m per day from oil and gas sales. That figure is likely to be higher now because since the invasion began oil prices have risen sharply.

By comparison, Russia is less exposed in the industries affected by sanctions. The country accounts for just 1.6% of global trade in physical goods and 0.4% of global cross-border banking transactions.

Trade with some non-Western countries, such as China, has also continued at pre-invasions levels in most sectors.

However, there is now evidence of some businesses headquartered in countries that have not backed sanctions, such as a division of China’s carmaker Geely, beginning to distance themselves from Moscow.

Mr Koepke says should this continue it would make Russia’s trade recovery more difficult.

“Even if the war was resolved today, there is going to be a carry-over effect at minimum three months before there is any talk of return to progress.”

The Data and Forensics team is a multi-skilled unit dedicated to providing transparent journalism from Sky News. We gather, analyse and visualise data to tell data-driven stories. We combine traditional reporting skills with advanced analysis of satellite images, social media and other open source information. Through multimedia storytelling we aim to better explain the world while also showing how our journalism is done.