The FTSE 100 company part-owned by Abramovich that has scarred the City

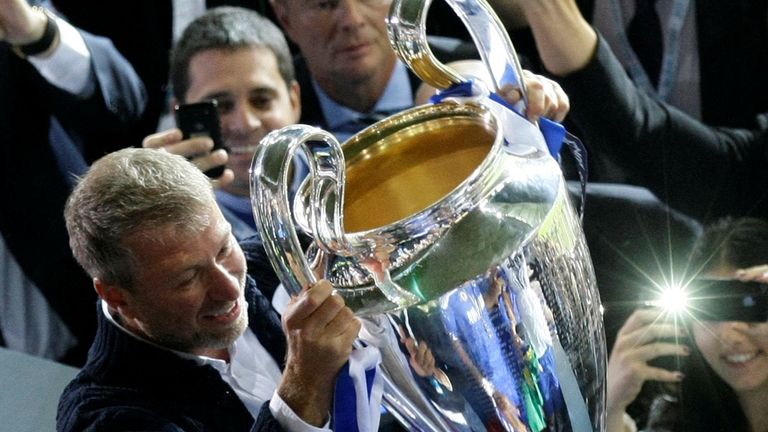

While most attention has focused on Chelsea FC, following the freeze on assets of its owner Roman Abramovich, rather less attention has been paid to another of the oligarch’s assets.

For Mr Abramovich is also the owner of a 28.64% stake in Evraz, the London-listed steel, coal mining and vanadium business based largely in Russia, but which also owns operations in the United States, Canada, the Czech Republic and Kazakhstan.

The company has been a member of the FTSE 100 since January 2018, obliging tracker funds in which millions of Britons are invested to buy its shares, but its fortunes are now unravelling at a speed almost without precedent for a member of the UK’s blue-chip index.

Read more: Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich sanctioned by UK – and Three suspends club sponsorship

On Friday morning, in the latest development, 10 of the company’s 11 directors resigned from its board, leaving Alexey Ivanov, its chief executive, as the last man standing.

The directors who have quit are an eclectic bunch and include Sir Michael Peat, the former private secretary to Prince Charles, and Eugene Shvidler, a billionaire oligarch who partnered with Abramovich in 1995 to buy the oil giant Sibneft for a knock-down price – the transaction which transformed the fortunes of both men and which provided the means for buying Chelsea eight years later.

Shvidler and Abramovich remain close business associates to this day.

Other Evraz directors to have stepped down include Eugene Tenenbaum, another Abramovich associate who sits on the Chelsea FC board, and Deborah Gudgeon, a former accountant with Deloitte who has served on the boards of a number of mining companies.

They also include Stephen Odell, a former executive vice president for global marketing, sales and service at Ford, where he worked for 37 years. The most recent addition to the board, Maria Gordon, a former executive at the fund manager Pimco, has also stepped down, having only become a director of Evraz at the beginning of last month.

The resignations are only the latest developments in a torrid few weeks for Evraz, which saw its stock market value peak in April last year at just under £5.9bn.

On 16 February, just days before Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, its shares were trading at 337p.

By Thursday last week, a mere 11 trading sessions later, those shares had lost 84% of their value. It is a destruction of value almost without precedent for a FTSE-100 member and sealed the company’s relegation from the index.

Things have moved pretty rapidly since. On Wednesday morning, Evraz issued a statement in which it insisted: “Although the imposition of international sanctions against Russia and the restrictions imposed by Russia are creating certain frictions in supply, logistics and financial flows, to date there has been no material direct impact on day-to-day operations, trading or the financial position of Evraz.”

But a sign that all was not well came when, just hours later, the company abruptly cancelled payment of its half year dividend. This was to have been paid to shareholders on 30 March and totalled $729m – a pay-out worth just under $209m, before tax, to Abramovich.

Evraz said that “given the uncertainties arising from the current situation in relation to Russia and Ukraine”, paying the dividend was no longer in the best interests of the company and its shareholders, an indication, perhaps, of the need to preserve cash.

Thursday morning brought news of the UK government’s sanctions of Abramovich, after which trading in the shares was suspended at the behest of the Financial Conduct Authority, pending clarification of the impact of the UK sanctions.

Crucially, the government’s justification for sanctioning Abramovich included this damning assertion: “Evraz is or has been involved in providing financial services, or making available funds, economic resources, goods or technology that could contribute to destabilising Ukraine or undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty or independence of Ukraine – which includes potentially supplying steel to the Russian military which may have been used in the production of tanks.”

Hours later, Evraz issued a statement in which it stressed that Abramovich was not, under company law, “as a person exercising the effective control of the company”, pointing out his inability to appoint or remove a majority of its directors or to ensure the company was run according to his wishes.

It argued that this meant the UK’s financial sanctions should not apply to the company itself.

The company also denied remarks about it in the government’s sanctions statement.

It added: “The company confirms that it supplies long steel to infrastructure and construction sectors only.”

But Friday morning’s boardroom exodus rather suggests that, despite the company’s best efforts to distance itself from Abramovich, it recognises that the game is up.

Evraz has not done itself any favours by failing to condemn the Russian government unequivocally for its invasion of Ukraine – something that has been done by most Western companies that have announced the suspension or closure of their Russian operations during recent days.

The statement, in line with previous ones, merely noted that “Evraz is deeply concerned and saddened by the Ukraine-Russia conflict and hopes that a peaceful resolution will be found soon”.

Those weasel words point to a reluctance at the company to antagonise the Russian president.

The next step, in all probability, will be that shares of Evraz are de-listed from the London Stock Exchange – a measure for which a number of politicians, most notably the former Conservative leader Sir Iain Duncan Smith, have been calling this week.

That would crystallise big losses for clients of a number of well-known institutional shareholders in Evraz that include Schroders, BlackRock, Vanguard and Pictet Asset Management.

Some of them would not have been shareholders had this giant company, which only listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2005, not been admitted to the FTSE 100.

With just 30% of its shares freely floating and available for outside investors to buy, with the rest controlled by Abramovich and his coterie, that should never have been allowed – and it is hoped the UK listing authority has learned a lesson from the affair.