Why John Lewis is now offering savings and investment services

The initial reaction to news that the John Lewis Partnership has begun offering savings and investment services is – what took it so long?

Just about every survey or opinion poll suggests John Lewis is one of the most, if not the most, trusted and admired brands in the country.

At the end of 2020, the pollster YouGov revealed the retailer had topped its Best Brand rankings in the UK for the fourth consecutive year, despite its stores being closed for much of the previous nine months and in spite of the partnership having recently announced 1,500 job cuts.

So this is an enormously resilient brand and one intimately trusted by consumers.

Providing investment services, where trust is more important than almost anything, is therefore a logical brand extension.

It is all the more logical given that John Lewis already offers credit services through its Partnership Card and also sells home, car and pet insurance.

The retailer cannot be accused of rushing its fences.

It launched a financial services arm in 2006 under the name Greenbee that was widely expected at the time to begin offering savings and investment products.

It never happened and the Greenbee brand was retired just four years later.

The initial product range will be quite a limited one.

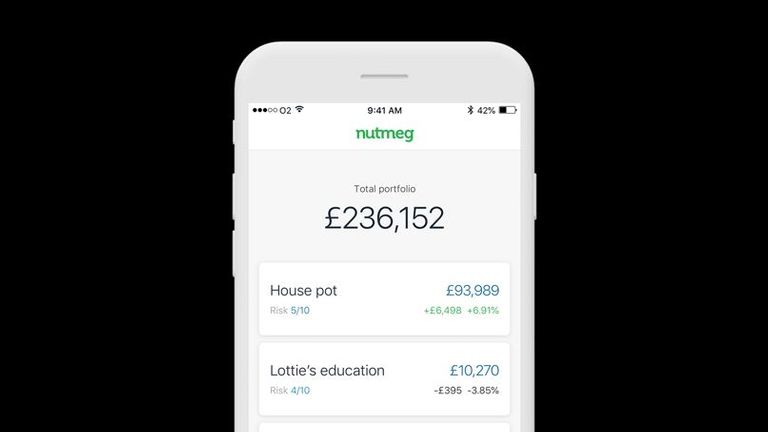

Provided in partnership with Nutmeg, the digital wealth manager and so-called “robo-advice” firm recently acquired by US banking colossus JP Morgan Chase, it comprises a Junior ISA, a stocks and shares ISA and, for those customers who have already used up their annual £20,000 ISA allowance, a general investment account.

All will be based around funds in the environmental, social and governance (ESG) field.

Robo-advisers are low-cost digital platforms which collect information from customers on the risk they are prepared to accept, along with their savings goals, before automatically investing their money accordingly.

Anyone expecting to be able to stroll into a John Lewis department store and sit down with a financial adviser, as they might obtain expert advice in the haberdashery department, is going to be disappointed.

The move, part of a drive to quadruple the size of the partnership’s financial services business during the next five years, is interesting in its timing.

It comes as a number of retailers have actually pared back their financial services businesses.

Tesco said earlier this year that it would be closing all of its current accounts, a service it launched seven years ago, by the end of November, having already closed the service to new accounts in 2019.

That year also saw the supermarket offload its mortgages business to Lloyds Banking Group for £3.8bn and saw its rival Sainsbury’s stop selling mortgages to new customers.

It has since been reported that Sainsbury’s is looking to sell its entire banking operation.

Marks & Spencer, meanwhile, is also to stop providing current accounts at the end of this month and has already begun closing its in-store branches although it has continued to offer credit cards, insurance, savings and loan services online.

The retrenchments speak volumes about the intensity of competition in services like current accounts and mortgages.

These services are dominated by the commercial banks and, even with their vast market shares, they have struggled to make sustainable profits from them at a time of near-zero interest rates.

That probably explains why John Lewis is targeting the potentially more profitable product area of savings and investments.

Yet this field is no less competitive.

A plethora of established investment platforms offer stocks and shares ISAs and other so-called “fund supermarket” services, among them Hargreaves Lansdown, AJ Bell, Fidelity and Interactive Investor.

These are all big, dominant players.

Hargreaves Lansdown alone has more than one million ISA account holders on its platform.

Meanwhile, the big four commercial banks – NatWest, Barclays, Lloyds and HSBC – all offer stocks and shares ISAs and, with customers achieving ever more nugatory returns from cash savings accounts, have been making a concerted push into the savings and investments space.

The sharp rise in stock markets during the last 12 months and the growing popularity of share trading among a younger generation of investors has fed into that.

Barclays teamed up in July last year with another robo-advice firm, Scalable Capital, to provide a digital wealth management service.

Meanwhile just this week Lloyds – also an established player in traditional wealth management via a three-year old partnership with the fund manager Schroders – announced it was buying Embark Group, a robo-advice provider, for £390m.

The Financial Conduct Authority predicted last year that all of the commercial banks will offer robo-advice services soon.

The regulator, in a report published in December, said: “It is expected that all the major retail banks will have an automated advice proposition within the next few years.

“Given their existing client base, retail banks will be able to market their services directly to their existing customers.

“Consumers may be more inclined to trust an established brand and the entry of retail banks into the market may attract more first-time investors.”

John Lewis is clearly hoping that, with the strength of its brand, the FCA’s logic will also apply to its savings and investment offerings.

That there is an addressable market out there is beyond dispute.

The FCA report noted that only 1.3% of UK adults had used a provider of automated online investment and pension services during the previous 12 months and said the assets under management accounted for less than 0.5% of the retail investment market.

The regulator also observed that, while there was more awareness of automated investment advice services, just 19% of adults knew about them.

It added: “Lack of brand awareness is still a barrier for consumers.”

So John Lewis is targeting a big market and the strength of its brand may prove to be a key factor in attracting customers.

The nagging question, though, is why it expects to make headway in this particular field when it has such little impact in a market, like insurance, in which it has been a player for 15 years now.