Why Putin’s war will mean higher inflation lasting for longer

Vladimir Putin’s decision to wage war on Ukraine threatens to turn what was an already uncomfortable inflationary situation into something far worse.

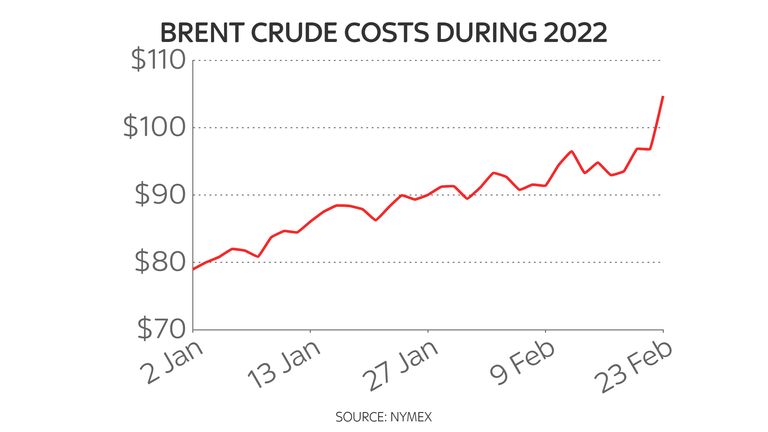

The most obvious consequence of the war will be in the price of hydrocarbons. The invasion has already sent the price of a barrel of Brent crude to as much as $105.33 this morning – a level last seen on 11 August 2014.

Higher oil prices effectively represent a tax on growth.

Ukraine ‘attacked from Russia, Belarus and Crimea’ – latest live updates

Most consumers associate it with higher household energy prices and higher petrol prices – the RAC has already warned of that in the near term.

But higher crude prices feed through to just about every other type of consumer good, including food and drink, via higher transport, packaging, manufacturing and processing costs.

The global markets strategy team at JP Morgan, the investment bank, point out that in 2014, when the price of crude was trading at an average of $100 per barrel, oil consumers spent some $3.4trn on crude and related products.

When it subsequently fell to an average of $45 per barrel, in 2016, those consumers were spending $1.6trn – in other words an income transfer of $1.8trn from oil producers to consumers.

They add: “This year, a recovery in oil demand along with our commodity strategists’ revised oil price forecasts would imply an increase in the spending on crude and related products by consumers from $1.4trn in 2020 to $3.6trn in 2022, an effective income transfer of $2.2trn or 2.3% of global GDP.”

That is a colossal transfer of wealth from consumers to oil and gas producers such as Saudi Arabia, the United States and, yes, Russia.

It is likely in particular to feed through to higher prices of goods manufactured in Germany, such as cars and machine tools, due to the country’s unusually high dependence on Russian gas to power its industry.

But Mr Putin’s war will have plenty of inflationary consequences elsewhere.

Financial markets react to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine – latest live updates

Ukraine is well known as the bread basket of Europe and together with Russia, during the current season, expected to account for 30% of world barley exports, 28% of global wheat exports and 19% of global corn exports.

They were together expected this year to account for 24% of world canola exports, 20% of global rapeseed production and half of the world’s sunflower products. All of these food and cooking staples can be expected to rise in price if Russian exports are embargoed and Ukrainian exports are disrupted.

The prices of all of these agricultural commodities have risen, continuing a trend already in train, with wheat prices up some 12% since the beginning of the year and corn prices up 14.5%. Wheat and oat futures prices have today risen by a further 5% or so.

The impact of some of these movements will be felt far and wide. For example, Ukraine overtook the United States last year as the bigger supplier to China of corn, a key foodstuff in the country.

Not all economies will suffer as a result. With some shipping companies already having decided against sailing from Ukraine, due to the risk of an invasion, big buyers of grain are seeking to source other supplies. Australian and American farmers look likely to be beneficiaries here although it is worth noting that the US wheat producing belt is currently suffering its worst drought since 2013 and this is likely to have an impact on crop yields.

The increase in costs of these soft commodities is likely to be more damaging for emerging markets, which spend more on food and cooking materials as a proportion of GDP, than the west.

As analysts at the consultancy Capital Economics noted today: “The pass-through from agricultural commodities prices to consumer prices tends to be quite weak, so this effect might add 0.2 to 0.4 percentage points to headline inflation in developed markets in the next few months.”

Read more:

‘Full-scale invasion’ – what do we know so far?

How strong is NATO’s position in Europe?

Fuel prices hitting record high as world economy reacts

More damaging to the west will be increases in the price of hard commodities as a result of the war.

Russia is the world’s third largest producer of nickel – one of the most important raw materials used in the production of electric vehicle batteries – the world’s second largest producer of platinum and the world’s sixth biggest producer of copper. The latter is the world’s most important industrial metal, due to the vast number of applications for which it is used, including building and construction, car manufacturing and electrical goods.

All of these sectors can expect to feel an inflationary impact and particularly if there are sanctions imposed on Russian exports. Russia is also the world’s sixth largest producer of aluminium, another important industrial metal, which was already in short supply. The country is also one of the world’s biggest diamond producers.

The state-owned Alrosa is the world’s biggest diamond mining and distribution company and accounts for some 27% of global diamond extraction. The price of these gems can, again, be expected to rise if embargoes are placed on Russian exports.

A further inflationary impact will be felt in the cost of doing trade. Airlines are already avoiding airspace in Ukraine and this will potentially push up the cost of flying – on top of the increased price of jet fuel – if they are forced to take longer routes.

Shipping routes could also be subject to disruption and this too will add to costs. There is already evidence of some shipping companies charging a premium to reflect the added risk of sailing in the vicinities of Russia and Ukraine.

While all of this sounds like bad news, it is important to keep things in context. The price of oil has already been at elevated levels for a while and so, on a year on year comparison, the headline rate of inflation may start to come off the boil in developed market economies as 2022 progresses – what economists refer to as ‘base effects’ in the jargon.

But it does mean that inflation is likely to remain higher for longer than economists had been forecasting. Capital Economics now expects inflation in advanced economies, such as the UK, to still be at an average of 4% by December – twice the level of the Bank of England’s target rate.

That raises the risk that central banks such as the US Federal Reserve and the Bank have to raise interest rates more dramatically than expected to keep inflation at bay.

And that, in turn, will impact global growth.

As things stand, though, the war is unlikely to tip the global economy into another recession. Most economies around the world are still in recovery mode following the pandemic and growing nicely.

It should also be stressed that even if the Russian economy is hurt by sanctions – something it has so far proved more than capable of withstanding – it is unlikely to have a wider impact on global growth.

For all of its importance in many global commodity markets, the GDP of Russia remains smaller than that of Italy, a country whose population is barely two-fifths its size.