Why Shell could be making $10bn exit from US shale operations

Life moves fast at Royal Dutch Shell these days.

Just three weeks ago, the oil and gas giant was ordered by a Dutch court to cut its carbon emissions more rapidly than the company itself had been planning to.

Shell’s chief executive, Ben van Beurden, responded last week with a promise that, although the company is appealing against the ruling, it will accelerate its transition away from fossil fuels.

Now it has emerged, through reporting by Reuters, that Shell is looking to sell some or all of its US shale operations in the Permian Basin – a region spanning Texas and New Mexico and which is famed for the quality of its oil deposits.

Shell owns some 260,000 acres in the Permian and its oil and gas production from the region last year was 193,000 barrels per day.

Reuters said that an asset sale could raise as much as $10bn.

Were Shell to sell the assets, which it bought in 2012 from US shale producer Chesapeake Energy for $1.9bn, it would represent something of a U-turn from the company.

Shell has reduced its Permian production during the last year, in an attempt to save money, but Mr van Beurden said as recently as February this year that the Permian Basin was “a high quality operation” in which it would continue to invest.

This decision will undoubtedly, then, spark speculation that the sale decision has been prompted by the requirement to move away from fossil fuels more quickly.

Shell’s Permian Basin assets account for about 6% of its entire oil and gas production and the high carbon intensity of shale production means that offloading these assets would have a disproportionate impact on Shell’s drive to decarbonise.

There are, however, other good reasons why Shell might have decided to review the future of these assets now.

The first is the state of its finances.

In common with the rest of the oil and gas sector, Shell suffered a battering during the pandemic, forcing it to cut its dividend – one of the most important to pension funds – for the first time since the Second World War.

It then wrote down the value of its assets to the tune of billions of dollars.

A $10bn asset sale would therefore be very welcome and not least because some of the sale proceeds could be applied to paying down debt.

Shell has committed to reducing its net debt, which stood at $71bn at the end of March, to below $65bn.

A sale of this magnitude would also bring in capital that could be deployed on the energy transition.

Shell, which is also in the process of selling all but one of its refineries in the US, may also be calculating that this is a good time to be selling.

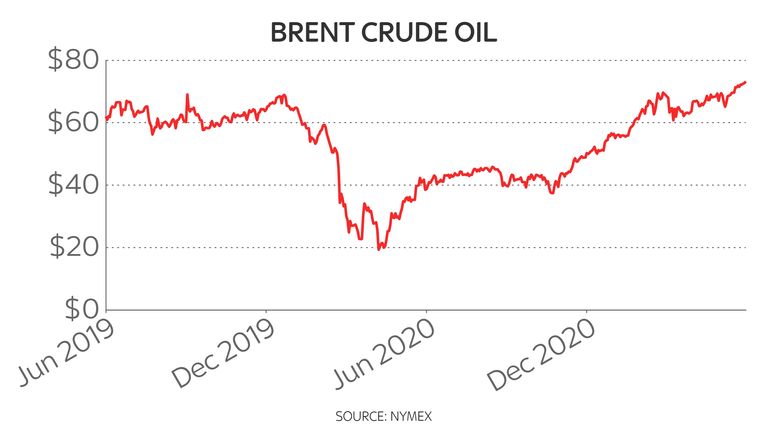

The price of Brent crude this morning hit $73.70 per barrel, its highest level since April 2019, while WTI, the US equivalent of Brent, has just hit its highest level since October 2018.

That has given oil and gas companies the confidence to think about the future and plan accordingly.

Most shale oil producers in the Permian Basin, the lowest-cost oilfield to have participated in the fracking boom, require an oil price of around $49 a barrel to break even.

So a price north of $70 a barrel enhances the attraction of assets there.

At the same time, a wave of consolidation is sweeping the US shale industry.

The process got underway when, in April 2019, Occidental Petroleum agreed to buy its rival Anadarko for $57bn in what turned out to be one of the most disastrous acquisitions in US oil and gas history.

The subsequent collapse in oil prices during the pandemic brought a number of players to their knees, most notably Chesapeake, a pioneer in US shale.

However, in a sector where scale counts, there remains industrial logic in companies pooling their US shale assets.

There were two big deals in the sector last year, with Chevron buying Noble Energy for $5bn and ConocoPhilips agreeing to buy Concho Resources for $9.7bn, but the deals have kept on coming in 2021.

Last month saw the US shale players Cabot Oil & Gas agree to merge with Cimarex Energy, a shale producer based in the Permian, to create a $14bn player.

This month has already seen Colorado-based Civitas Resources – itself formed from a merger announced earlier this year – agree to buy its cross-state rival Crestone Peak Resources for $1bn.

Meanwhile Houston-based Independence Energy, which is owned by the private equity giant KKR, agreed to merge with Fort Worth-based Contango Oil and Gas, creating a $5bn business.

Contango itself had completed no fewer than four big acquisitions during the previous 18 months.

Few industry commentators expect the consolidation process to have finished and there would be no shortage of buyers for Shell’s Permian Basin assets.

Shell may also be seeking to dispose of its US shale assets before competitors like Chevron and Exxon, both of whom are looking to trim their portfolios in the sector, even though Exxon doubled the size of its oil and gas holdings in the Permian Basin through a $5.6bn deal only as recently as 2017.

Occidental is also in the process of selling some of its Permian assets to reduce its debt.

So there are a number of reasons why a sale of its Permian assets would make sense for Shell.

But that is not to say it would necessarily be the right thing for shareholders.

Shell would probably have preferred to keep these highly cash generative assets had it not just been told to accelerate its transition away from fossil fuels.